Rocket Street Bridge

Bridges are not just functional structures, they are often iconic landmarks that embody the essence of engineering innovation and architectural beauty. One such gem is the Rocket Street Bridge, a breathtaking example of a Pratt truss-designed bridge located in South Bathurst, New South Wales. While its exact opening date remains a mystery to me, the bridge's significance lies in its role as a connection between history, engineering, and aesthetic charm.

The Rocket Street Bridge is more than just a physical connection between two points, it's a bridge that connects history, engineering brilliance, and artistic finesse. With its Pratt truss design, influenced by George Cowdery's innovations and the Schweidler truss aesthetics, the bridge stands as a testament to the progress of engineering and design. As we traverse this remarkable structure, we are reminded that bridges are not mere conduits but rather symbols of human achievement that deserve our admiration and preservation.

A Journey through Time: The origins of the Rocket Street Bridge are rooted in the late 19th century when the railway was extended from Bathurst to Blayney in November 1876. Initially, the public access route from South Bathurst to Vale Road was a level crossing, serving its purpose but lacking the sophistication and infrastructure the region deserved. It wasn't until 1888 or 1889 that the Rocket Street Bridge came to life. The bridge has the date 1888 but a report on the Denison bridge for a Historic Engineering marker states 1889 was the year it opened. The bridge's construction date might be elusive, but its impact on the landscape and the community is undeniable.

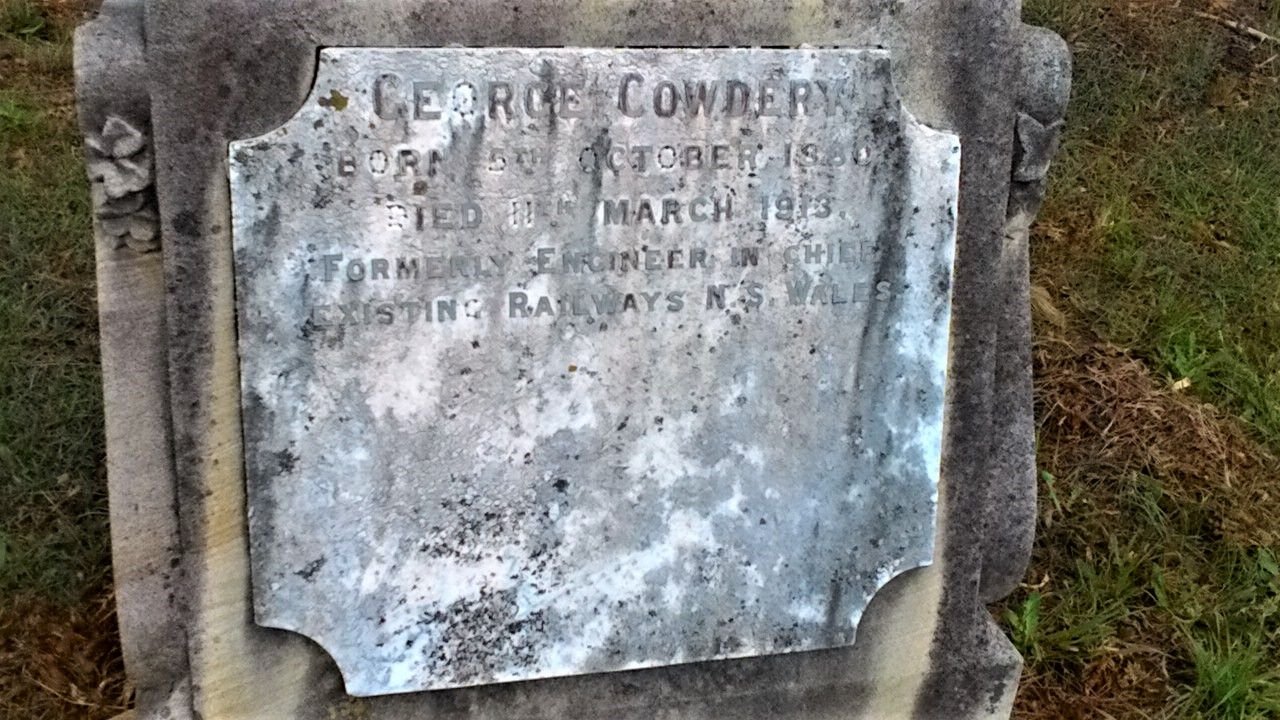

George Cowdery (1830 - 1913)- Notabel Railway Engineer

Supervising the construction of the Rocket Street Bridge was George Cowdery and his team. Cowdery, a prominent figure in New South Wales' railway development, introduced the Pratt truss into the railway system between 1885 and 1889. His inspiration stemmed from both European and American truss designs. What's interesting is that even though the Rocket Street Bridge is classified as a Pratt truss design, it exhibits striking similarities to the Schweidler truss design.

His legacy as a pioneering force in shaping New South Wales' railway systems endures, leaving an indelible imprint on the landscape of transportation infrastructure. Rooted in a family tradition of railway contracting, Cowdery's trajectory was marked by unwavering commitment, ingenious innovation, and a lifelong dedication to advancing the frontiers of engineering excellence.

An Inherited Heritage of Engineering: Emerging from a lineage steeped in railway contracting, George Cowdery inherited a fervor for engineering from his father, a custodian of railway contracting ventures undertaken by Messrs Betts and Macintosh in England. Immersed in colossal undertakings such as constructing significant British trunk lines, Cowdery's formative years were a playground for exposure to the intricacies of railroads. His involvement in building the illustrious Britannia Bridge, alongside the iconic Robert Stephenson, infused his aspirations with foundational experiences that stoked the flames of his ambitions.

The Journey to Australia: During the era of the Crimean War, George Cowdery embarked on a transformative odyssey to the shores of Australia. The stage was set for railways to etch their routes across the continent, offering Cowdery a blank canvas for his visionary insights. By 1863, he assumed the mantle of a district engineer for the Great Southern Railway under the guidance of John Whitton. His oversight of pivotal undertakings, including the construction of the pioneering Picton and Mittagong tunnels, heralded the dawn of tunneling practices in New South Wales.

Championing Vision and Ingenuity: As his influence swelled, George Cowdery's tenure amplified in impact. Spearheading the evolution of the Great Western Line, he presided over the iconic construction of the Zig Zag. By 1880, he ascended to the role of chief assistant to William Mason, ascending further to the mantle of engineer-in-chief for existing lines. His visionary stewardship bore fruit in the establishment of the enduring Eveleigh workshops and the division of the railway system into districts, optimizing efficiency and collaborative synergy.

BIRTH: 5 October 1830 Portsea, Hampshire, England

DEATH: 11 March 1913 (aged 82) Blackheath, Blue Mountains City, New South Wales, Australia

BURIAL: Blackheath Cemetery, Blue Mountains City, New South Wales, Australia (Plot: Church of England)

Photo from Find A Grave Website

A Legacy Engraved in Time: The passing of George Cowdery leaves a legacy that transcends the realm of railways. His contributions traversed the rails, culminating in blueprints for the Lowestoft Lighthouse in England that continue to endure.

George Cowdery's narrative is one of tenacity, transformation, and resolute dedication to propelling the field of railway engineering. From his role in the Britannia Bridge to the evolution of New South Wales' railway systems, his imprint is emblematic of progress and devotion. As his legacy weaves its way through time via the structures he helped shape and the lives he inspired, Cowdery's name will forever remain synonymous with advancement, ingenuity, and the art of engineering.

The initials of Queen Victoria – VR – which stands for Victoria Regina. Regina is Queen in Latin.

The Marvel of Pratt Truss Design: Standing as a testament to engineering prowess, the Rocket Street Bridge boasts a 135-foot Pratt truss design. The Pratt truss design incorporates vertical members and diagonals that slope down toward the center, a characteristic opposite to the Howe truss. This design innovation was the brainchild of Thomas and Caleb Pratt, who invented the Pratt truss in 1844. The Pratt truss configuration allowed for efficient weight distribution, making it a popular choice as bridges transitioned from wood to metal.

The Schweidler Truss Influence: The Schweidler truss design, with its distinct "hogs back" top chord, appears to have left an indelible mark on the Rocket Street Bridge's aesthetics. The Schweidler truss, characterized by its polygonal top chord, offers a visual appeal that echoes across time and space. This amalgamation of Pratt and Schweidler truss elements gives the bridge a unique charm that captures the imagination of those who cross its path.

View of the Rocket Street Bridge from a steam train.

Locations of Bathurst’s four significant colonial bridges.

Graffiti: Art or Vandalism?

View of the Rocket Street Bridge from a train. Note the graffiti on the red brick work. (Graffiti artist unknown)

Graffiti a form of visual expression that involves painting or drawing on public spaces, has long been a subject of intense debate. Is it a legitimate form of art, a reflection of urban culture, or simply a form of vandalism that defaces public property? This contentious issue has sparked discussions among artists, policymakers, and the public alike. While some argue that graffiti should be considered art, a closer examination reveals that its detrimental aspects often overshadow its artistic potential. In this article, we will delve into the arguments on both sides of the debate, taking a closer look at the renowned graffiti artist Banksy, the cost of graffiti removal, and ultimately conclude that graffiti is more accurately categorized as vandalism.

The Artistic Perspective and Banksy's Impact: Advocates of graffiti as art emphasize its ability to convey powerful messages, challenge societal norms, and provide an outlet for marginalized voices. One of the most prominent figures in this regard is Banksy, whose thought-provoking artworks have captured global attention. Banksy's creations often tackle political, social, and environmental issues, using public spaces as his canvas. His works have been lauded for their ingenuity, incisiveness, and ability to spark conversations about important topics. The emergence of artists like Banksy has fueled the argument that graffiti is a form of art capable of influencing and engaging communities on a meaningful level.

The Vandalism Argument: Balancing Creativity and Property Rights: While Banksy's work might exemplify the artistic potential of graffiti, the core concerns regarding vandalism remain pertinent. Vandalism, by definition, involves the intentional destruction or damage to public or private property without consent. Despite Banksy's fame, the fact that his art often appears without proper authorization from property owners or authorities still raises valid questions about its legitimacy. The debate around graffiti hinges on the tension between artistic expression and property rights, and this tension is particularly evident in the case of Banksy's works.

The Cost of Cleanup, A Reality Check: A significant aspect of the graffiti debate often overlooked is the substantial financial burden it places on communities. In Australia, the cost of graffiti removal is staggering. The country spends around $2 billion annually to combat graffiti-related defacement, with Melbourne alone expending approximately $100 million on graffiti removal each year. These funds could be directed toward more constructive purposes, such as community development, infrastructure, and education. The financial strain of graffiti removal underscores the negative consequences of unchecked artistic expression on public spaces.

In the ongoing debate over whether graffiti should be considered art or vandalism, the mysterious figure of Banksy adds an intriguing dimension. His art highlights the potential of graffiti to convey profound messages and influence society. However, the unresolved issue of property rights and the unsanctioned nature of much graffiti cannot be overlooked. The substantial costs associated with graffiti removal, as evidenced by Australia's expenditures, serve as a reality check. While his work has pushed the boundaries of conventional art, the financial and aesthetic concerns surrounding graffiti's impact on communities place it within the realm of vandalism. As we continue to grapple with this complex issue, finding ways to channel artistic expression through legal and collaborative means remains essential to strike a balance between creativity and responsible urban development.

Graffiti on the Rocket Street Bridge plaque stating when it was built in 1888 (135 years ago).

As always please leave a comment below if I have any information incorrect so I can amend it or if there are any key factors I have missed that I should add to this blog post.

Nadine Travels West.